FROM SAFETY PERFORMANCE TO HUMAN CAPITAL ROI:

A STRATEGIC BLUEPRINT FOR SUSTAINABLE CREW DEVELOPMENT

Introduction: The Shifting Tides of Maritime Human Capital – From Cost Center to Value Driver

The global maritime industry stands at a confluence of three powerful and transformative currents: the disruptive force of decarbonization technologies, the imminent dawn of widespread automation, and a profound, industry-wide re-evaluation of the human element. This report argues that the traditional crewing model—a paradigm historically focused on minimizing operational costs and ensuring minimal regulatory compliance—is not only outdated but also represents a direct and escalating threat to the long-term viability of any shipping enterprise. The prevailing “illusion” is that cutting crew-related costs is a direct path to enhanced profitability; the critical “insight” is that strategic, sustained investment in human capital is the only viable path to generating sustainable Return on Investment (ROI) in the modern shipping era.

The central thesis of this analysis is to demonstrate that by proactively navigating the complex and rapidly evolving regulatory horizon, embracing the strategic principles of “Human Sustainability,” and learning from the proven successes of industry pioneers, shipping companies can build a future-ready, high-quality crew. Such a crew ceases to be a line item on a balance sheet. It becomes a primary driver of value, delivering a direct and measurable return on investment through superior safety records, enhanced operational efficiency, heightened client satisfaction, and critically, the attraction and retention of irreplaceable talent.

This report is structured in four distinct parts to provide a comprehensive strategic framework. Part I analyzes the unavoidable regulatory and technological landscape that is forcing a fundamental rethink of seafarer competency and training. Part II defines and operationalizes the new strategic paradigm of Human Sustainability, positioning it as a core business imperative rather than a peripheral corporate social responsibility initiative. Part III grounds these advanced concepts in the tangible reality of real-world case studies, examining companies that have successfully implemented these strategies and reaped the commercial rewards. Finally, Part IV synthesizes all preceding analysis into a comprehensive strategic blueprint, offering an actionable framework for senior leadership to implement these transformative changes within their own organizations.

Part I: The Unavoidable Horizon: Navigating a New Regulatory and Technological Era

The external pressures compelling a fundamental shift in crewing strategy are no longer distant possibilities; they are present and accelerating realities. A detailed examination of the impending regulatory and technological changes reveals that a reactive, compliance-focused posture is insufficient. The focus must shift from merely understanding the letter of the new laws to anticipating their second and third-order strategic implications for human capital management.

Subsection 1.1: The Decarbonization Mandate & The Multi-Fuel Competency Challenge

The global mandate for decarbonization, spearheaded by the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) revised greenhouse gas (GHG) strategy, is the primary catalyst reshaping the technical landscape of shipping.1 This strategy is not a distant goal but an active driver of immediate technological change, pushing the industry toward a multi-fuel future where scalable zero-emission fuels, such as e-ammonia and e-methanol, are expected to become dominant compliance options.1 This transition necessitates a cascade of significant updates to foundational safety codes, directly impacting the required competencies of seafarers.

The IMO’s Maritime Safety Committee (MSC), at its 110th session, has already taken decisive steps. It adopted draft amendments to SOLAS Chapter II-1 to clarify that the International Code of Safety for Ships using Gases or other Low-flashpoint Fuels (IGF Code) applies to all gaseous fuels, regardless of their flashpoint, not just those traditionally defined as “low-flashpoint”.2 This seemingly technical clarification has profound training implications, broadening the scope of mandatory specialized knowledge. Furthermore, the committee is actively addressing regulatory barriers to new technologies like onboard carbon capture and storage (CCS) and even updating the Code of Safety for Nuclear Merchant Ships to account for technological advances.2

This proliferation of fuel and propulsion technologies shatters the long-held paradigm of a universally transferable skillset for marine engineers and deck officers. The era of the “universal seafarer,” whose core competencies were largely interchangeable between vessels running on conventional heavy fuel oil or marine diesel, is definitively over. The emerging reality is one of hyper-specialization. Each alternative fuel—be it Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), methanol, ammonia, or hydrogen—comes with a unique set of handling properties, toxicity profiles, bunkering procedures, firefighting requirements, and emergency response protocols. Consequently, a Chief Engineer expertly certified for an LNG-fueled vessel is not, by default, competent to manage the engine room of an ammonia-fueled ship.

This fragmentation of required knowledge leads to a critical second-order implication for crew management. Manning departments can no longer rely on a generic pool of available talent. They must evolve to develop and maintain sophisticated “competency matrices” that meticulously map the specific, certified skills of individual seafarers to the unique technical requirements of each vessel in the fleet. This, in turn, creates a third-order effect: the formation of talent “silos.” The industry will witness the emergence of distinct, and not easily interchangeable, pools of officers with certified experience on next-generation fuels. This will inevitably lead to intense competition for this niche talent, driving up wages, training costs, and recruitment complexity. Companies that fail to anticipate this shift will find themselves at a severe commercial disadvantage, struggling to crew their advanced vessels. Conversely, organizations that proactively build these specialized talent pipelines in-house, as demonstrated by crewing agencies like AB Crewing who successfully developed a dedicated program to qualify Romanian seafarers for complex LNG carriers when a shortage was identified, will secure a significant and sustainable competitive advantage.5

Subsection 1.2: The Dawn of Automation & The Redefined Role of the Seafarer

Parallel to the fuel transition is the steady advance of automation. The industry is making significant progress on the development of a non-mandatory Code of Safety for Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS Code), with a target finalization date of 2026. Crucially, the IMO’s intent is for this code to become mandatory once sufficient experience has been gained from its application, signaling a clear long-term trajectory.2 At MSC 110, 18 chapters of the MASS Code were finalized, a testament to the rapid progress in defining the technical and operational parameters for autonomous vessels. However, the most telling detail is that the chapter left to be finalized is the one concerning the “human element”.2

This is not a simple procedural delay; it is a symptom of the industry’s profound strategic uncertainty regarding the future role of humans in an increasingly automated maritime ecosystem. While the technical aspects of automation—such as remote navigation, automated machinery control, and sensor fusion—are advancing rapidly, the industry has yet to coalesce around a clear definition of the new skillsets required for the “human in the loop.” This role may be onboard, as a systems supervisor and crisis manager, or located thousands of miles away in a shore-side control center as a remote operator. The Sub-Committee on Human Element, Training and Watchkeeping (HTW) has noted that detailed training requirements for MASS operations will only be developed after the technical requirements of the code have been finalized, creating a dangerous vacuum.6

This situation presents a clear strategic challenge. The core challenge of automation is not technological; it is human. The second-order implication is that companies cannot afford to wait for the IMO to define these future roles and training standards. Those that do will fall years behind the curve. Proactive industry leaders must begin developing their own pilot programs and training frameworks now, focusing on a new suite of competencies that includes data analytics, advanced systems diagnostics, cybersecurity protocols, and remote crisis management.

The third-order implication of this shift is a fundamental bifurcation of the maritime workforce. Automation will progressively reduce the demand for traditional roles centered on manual labor and routine watchkeeping. Simultaneously, it will create a massive and urgent demand for a new class of highly-educated, technologically-savvy professionals who can be best described as “maritime systems engineers.” This new reality poses a direct threat to the traditional maritime career path, which has long enabled ratings to progress to senior officer ranks. A new pathway, and indeed a new talent pipeline, is required. This necessitates a fundamental rethinking of maritime education and training (MET), starting as early as the secondary school level, to cultivate interest and build foundational skills in technology and systems thinking, thereby ensuring a sustainable supply of talent for these new, critical roles.7

Subsection 1.3: STCW in Transition – The Risk of Regulatory Lag

The International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW) has been the bedrock of global maritime competency standards for decades. Recognizing the pace of change, the IMO has initiated a comprehensive review of the STCW Convention and Code. The first phase of this review has already identified over 500 gaps and inconsistencies that need to be addressed.6 However, the updated roadmap for this comprehensive revision targets completion not until 2031.6

This timeline creates a significant and perilous “competency chasm.” New technologies and alternative fuels are being introduced at a rapid pace, with many related amendments to codes like SOLAS, IGF, and IMSBC having entry-into-force dates between 2027 and 2029.2 This means the industry will face a period of at least five to seven years, and likely longer, where the global standard for training (STCW) lags dangerously behind the technology being deployed on the high seas. During this period, a seafarer holding a certificate that is fully “compliant” with the current STCW code may be fundamentally “incompetent” to safely operate a vessel equipped with the latest propulsion systems or automation technology.

This regulatory lag renders a strategy of passive compliance obsolete and transforms proactive training from an optional extra into a commercial imperative. The second-order implication is that key industry stakeholders, particularly risk-averse charterers and the major oil companies, will not accept minimum STCW compliance as a sufficient guarantee of operational safety and quality. They will demand verifiable proof of advanced, technology-specific training that goes far beyond the STCW baseline. This is precisely the dynamic observed in the case of Transpetrol, where the stringent demands of oil majors for documented proof of competency were the primary driver for the evolution of their advanced crew training and evaluation systems.9

The third-order implication is the emergence of a two-tiered market for shipping services. Tier 1 will consist of shipowners and managers who have invested in robust, in-house, data-verified training programs that address the competency chasm head-on. These companies will be able to command premium charter rates, secure long-term contracts with blue-chip clients, and benefit from lower insurance premiums. Tier 2 will be comprised of companies that wait for the STCW revision in 2031. These operators will likely face limited market access, punitive insurance costs, and significant difficulty in attracting and retaining the high-quality talent required to operate a modern fleet. In this new environment, the ability to prove crew competence beyond the certificate will become one of the most critical commercial differentiators.

Table 1: Key Upcoming IMO Regulatory Changes and Their Strategic Crewing Implications

|

Regulatory Instrument/Amendment |

Key Provisions/Changes | Target Adoption/Entry-into-Force Date | Direct Competency Impact (1st Order) |

Strategic Crewing Implication (2nd/3rd Order) |

| MASS Code | Establishes a goal-based framework for Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships, covering both autonomous and remote operations. 2 | Finalization targeted for 2026; intended to become mandatory after an experience-building phase. 6 | Need for new skills in remote operation, systems supervision, data analysis, and cybersecurity. | Bifurcation of the workforce into high-skill tech roles and low-skill manual roles; necessitates new career paths and a fundamental rethink of maritime education. |

| IGF Code Amendments | Clarifies application to all “gaseous fuels,” not just “low-flashpoint fuels,” introducing a new definition. 3 | Intended entry-into-force date of 1 July 2028. 4 | Mandatory, specialized training on the unique safety and handling protocols for a wider range of fuels (e.g., ammonia, hydrogen). | Creation of fuel-specific talent silos; increased competition and wage pressure for officers with certified experience on next-generation fuels. |

| STCW Comprehensive Review | A full review of the STCW Convention and Code to address over 500 identified gaps and incorporate new technologies. 6 | Roadmap targets completion in 2031. 6 | Future changes to all levels of seafarer certification, training standards, and watchkeeping requirements. | A significant “competency chasm” where STCW compliance will not equal operational competence; proactive, “beyond-STCW” training becomes a commercial necessity. |

| SOLAS Ch. V – Pilot Transfer | Introduces new mandatory performance standards for the design, manufacture, installation, and maintenance of pilot transfer arrangements. 2 | Applies to new installations from 1 Jan 2028; retroactive compliance required by first survey after 1 Jan 2029. 3 | Required familiarization and training for all crew on new equipment standards, inspection routines, and maintenance procedures. | Heightened focus on procedural discipline and safety culture; failure to comply carries significant operational and reputational risk. |

| “One Ship, One Code” Principle | Ongoing debate on whether gas carriers using alternative fuels should comply with the IGC Code, the IGF Code, or both. 4 | Guidelines to be developed; no firm date. 4 | Potential need for senior officers on gas carriers to be dual-certified or deeply familiar with two complex technical codes simultaneously. | Increased training burden and complexity for a highly specialized sector; further deepens the specialization required of top-tier officers. |

Part II: Beyond Compliance: Embracing Human Sustainability as a Core Business Strategy

The immense challenges outlined in the regulatory and technological horizon cannot be met by simply updating training manuals or purchasing new simulators. They demand a fundamental cultural and strategic shift within shipping organizations. This section transitions from the external pressures forcing change to the internal, cultural response required to thrive. It defines and operationalizes the concept of “Human Sustainability,” arguing that it is not a philanthropic sideline but the most effective strategic framework for attracting, developing, and retaining the high-quality talent essential for future success.

Subsection 2.1: Defining the New Paradigm – Human Sustainability as a Business Imperative

The concept of “Human Sustainability” is being championed by forward-thinking bodies like the Global Maritime Forum (GMF). It is defined as a concerted effort to create a maritime industry where every individual can expect to “work in a safe environment and be treated with dignity and respect”.10 This vision extends far beyond basic welfare and compliance with the Maritime Labour Convention. It is explicitly positioned as a “business imperative,” essential for the long-term health of the industry.12 The GMF identifies several critical risks that this paradigm seeks to address: working conditions that are falling behind other industries, significant challenges to health and safety (particularly mental health and fatigue), and a systemic failure to attract, retain, and upskill enough maritime professionals to meet the needs of global supply chains.12 Without addressing these human factors, the industry faces a potential workforce crisis that could put the entire global trade system at risk.11

This reframing is critical. The traditional management perspective often views crew welfare, mental health support, and diversity initiatives as “soft” issues or, more cynically, as costs to be minimized. The Human Sustainability framework turns this logic on its head, repositioning these elements as core functions of strategic risk management for a company’s most vital asset: its skilled labor force.

The logic proceeds in a clear sequence. Part I of this report established that the demand for highly skilled, technologically adept, and specialized seafarers is increasing at an exponential rate. Simultaneously, the maritime industry faces intense and growing competition for this talent from more attractive shore-based sectors, and it is plagued by systemic issues of attraction and retention, often stemming from poor working conditions and a disconnect from modern employee expectations.12 A 2022 GMF survey highlighted that “workforce and skill shortages” were a rising concern among industry leaders.14 This confluence of rising demand and constrained supply creates a classic supply-demand crisis, which constitutes a major, quantifiable business risk.

Therefore, investing in Human Sustainability—through better living conditions, robust mental health support, an inclusive and respectful culture, and clear career paths—is not merely “the right thing to do.” It is a direct, strategic intervention to secure a stable, motivated, and loyal long-term supply of talent. It is the most effective method of de-risking future operations against the threat of a critical skills shortage. The third-order implication is that companies that become recognized leaders in Human Sustainability will become “employers of choice.” This status will grant them a powerful competitive advantage, resulting in lower recruitment costs, significantly higher retention rates, and privileged access to the top percentile of maritime talent. This, in turn, creates a self-reinforcing cycle of operational excellence, superior safety performance, and enhanced profitability, making these companies more attractive to charterers, investors, and insurers who increasingly utilize Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria in their decision-making.

Subsection 2.2: The Six Enablers of Sustainable Crewing – An Operational Blueprint

To move Human Sustainability from an abstract concept to an executable strategy, the GMF’s Diversity@Sea initiative has developed an operational blueprint. Based on an extensive two-year pilot project that gathered over 50,000 data points from more than 400 seafarers, the project identified six key “enablers” of sustainable crewing.15 These are not theoretical ideals but practical levers that companies can pull to create a more attractive and effective work environment at sea. The six enablers are:

- Transparent career and promotion pathways.

- Inclusive leadership and psychological safety.

- Fit-for-purpose data systems to guide HR and crewing.

- Cross-functional collaboration among owners, managers, and charterers.

- Wellbeing practices embedded into crewing.

- Trust-building mechanisms across ranks and nationalities. 15

While all six are interconnected and essential, a deeper analysis reveals that one enabler serves as the foundational element upon which the others are built: “fit-for-purpose data systems.” The traditional crewing model, which often relies on paper certificates, manually tracked sea-time, and subjective annual appraisals, represents a “black box” of shipboard HR. This analog approach is wholly inadequate for managing the complex competency matrices, diverse career paths, and nuanced performance metrics of the modern maritime workforce. It is a significant and often overlooked liability.

Without robust data, career pathways (Enabler 1) remain opaque and subject to bias. The effectiveness of leadership (Enabler 2) cannot be objectively measured or improved. Wellbeing interventions (Enabler 5) cannot be targeted or their impact assessed. And building trust (Enabler 6) becomes exceptionally difficult in an environment governed by subjectivity. The Transpetrol case study provides a perfect illustration of this principle in action.9 The cornerstone of their celebrated success in crew retention and development was the implementation of a data-driven Crew Evaluation System (CES). This system provided the objective, verifiable data that made their training programs effective and their promotion pathways transparent and fair.

The second-order implication is clear: shipping companies must make a strategic investment in modern Human Capital Management Systems (HCMS). These systems must be capable of tracking granular skills, monitoring the effectiveness of specific training modules, capturing objective performance metrics, and mapping individual career aspirations. Such an investment is transformative, elevating the crewing department from a reactive, administrative function focused on logistics to a proactive, strategic talent management function capable of forecasting future needs and developing the workforce accordingly. The third-order implication is that the data generated by these systems will become a powerful source of competitive intelligence. Companies will gain the ability to accurately predict future skill shortages within their fleet, identify high-potential leaders at an early stage, and optimize their training budgets for maximum ROI. This data-driven approach will create a significant and enduring advantage over competitors who remain reliant on outdated, analog methods.

Subsection 2.3: The Business Case for Well-being – From Fatigue Management to Psychological Safety

The concept of well-being at sea is evolving rapidly. Key GMF initiatives, such as the Neptune Principles, have moved the conversation beyond basic physical safety to encompass critical areas like mental health, access to shore leave, and social connectivity.10 A core tenet of this new approach is the need to move beyond statutory minimum manning requirements, which are often inadequate, and instead staff vessels at levels that ensure sustainable work/rest hours and mitigate the pervasive and dangerous issue of fatigue.12

Within this broader discussion of well-being, the concept of “psychological safety” has emerged as a paramount concern. Defined as a workplace environment free from bullying and harassment, where every individual feels safe to speak up, ask questions, and report errors without fear of humiliation or retaliation, psychological safety is identified as a core component of inclusive leadership.12

In the high-risk, technologically complex environment of a modern vessel, human error remains the single greatest threat. The Almi Tankers case study acknowledged the industry-wide finding that human error is a causal factor in approximately 75% of incidents and accidents.16 Psychological safety is arguably the single most important cultural factor in preventing a minor human error from escalating into a catastrophic disaster. A culture that lacks psychological safety is one where a junior officer is afraid to question a senior officer’s navigational decision, even when they spot a clear and present danger. It is an environment where a rating hesitates to report a potential safety breach for fear of being labeled a troublemaker. This dynamic is a well-documented root cause of many of the maritime industry’s most tragic accidents.

The GMF’s strategic focus on this issue, coupled with the practical example of Almi Tankers’ investment in shifting their leadership style from “command and control” to a more “empowering” model, directly addresses this fundamental risk.12 The second-order implication is that investing in leadership training that specifically fosters psychological safety is not a “soft skill” expense. It is a direct and highly effective investment in operational risk reduction and organizational integrity. From a purely financial perspective, it is far cheaper to train a captain to listen effectively than it is to pay for the salvage, environmental cleanup, and reputational damage resulting from a grounding or collision.

Looking ahead, the third-order implication is that as vessels become even more complex with the introduction of new fuels and advanced automation, the potential consequences of a single, uncorrected human error will grow exponentially. A proven, demonstrable culture of psychological safety will cease to be a desirable attribute and will become a non-negotiable prerequisite for doing business. It will be a key factor in vetting processes, a determinant of insurance premiums, and a critical element in securing charters with top-tier clients, thereby directly impacting a company’s commercial viability.

Part III: From Theory to Practice: Case Studies in High-Performance Crew Development

The strategic concepts of navigating regulatory change and embedding Human Sustainability can seem abstract. However, an examination of industry pioneers provides concrete evidence that these investments are not only practical but also yield tangible, measurable returns. These case studies bridge the gap between strategic theory and operational execution, demonstrating how a focus on human capital directly drives commercial success.

Subsection 3.1: The Transpetrol Model – Engineering Loyalty Through Data-Driven Competency

Transpetrol, a Belgium-based independent tanker owner, provides a masterclass in transforming crew management from a cost center into a value-creating engine. The company’s journey began with a fundamental shift, driven by the exacting demands of oil major clients, from a culture of undocumented, “on the job” training to a highly structured, documented, and verifiable system.9 This evolution was not about simply ticking boxes; it was about proving competence in a world that increasingly demands evidence.

The cornerstone of their model is the pioneering use of a Crew Evaluation System (CES). Initially employed as a standard recruitment tool, Transpetrol innovatively expanded its application to cover the entire career lifecycle of a seafarer. The CES is now used to vet candidates for promotion, to assess the readiness of cadets for officer positions, for regular biennial assessments of all crew members regardless of rank, and to prescribe targeted retraining for any identified knowledge gaps.9 This system created what was previously missing for many seafarers: a clear, objective, and transparent career development guideline. It provided a roadmap for progression, complementing formal certificates and subjective appraisals with measurable data.9

The results of this data-driven approach have been remarkable. Transpetrol achieved an impressive 95% completion rate for its training programs and, most critically, fostered an “extremely high” retention rate among its seafarers.9 This created a “virtuous circle”: the high retention rate gave the company the confidence to invest heavily in training its junior officers, knowing that the investment would not be lost to competitors. In turn, the company’s demonstrated commitment to their career development engendered deep loyalty from the crew.9

The Transpetrol model is a powerful, real-world application of the “six enablers” of sustainable crewing. Their CES is the quintessential “fit-for-purpose data system” (Enabler 3) that makes “transparent career pathways” (Enabler 1) a tangible reality. The significant investment in high-quality training is a core “wellbeing practice” (Enabler 5) that serves as a powerful motivator and builds profound “trust” (Enabler 6) between the company and its crew. The key takeaway from this case is that data is the currency of trust and the key to unlocking retention. By making competency, performance, and career progression objective and measurable, Transpetrol effectively removed the ambiguity and potential for bias that can erode morale, demonstrating a genuine commitment to seafarer development that was reciprocated with exceptional loyalty and performance.

Subsection 3.2: The Almi Tankers Transformation – Cultivating Leadership to Drive Business Performance

Almi Tankers S.A. offers the ultimate proof of the Human Capital ROI model, drawing a direct and undeniable line from investment in leadership culture to concrete commercial success. Recognizing the limitations of a traditional maritime hierarchy, the company’s leadership identified a strategic need to evolve from a top-down, “command and control” style to a more “empowering, team-led leadership culture”.16 This was not a vague aspiration but a targeted business strategy aimed at enhancing safety, improving performance, and meeting the complex challenges of the future.

To achieve this transformation, Almi Tankers commissioned a bespoke “High Performance Leadership Programme” in collaboration with Saïd Business School, University of Oxford. This was not a one-off seminar but an intensive, multi-module program involving nearly half of the company’s head office personnel, including senior management, port captains, and first-line officers.16 The program was deeply practical, incorporating individual coaching sessions and focusing on developing self-awareness, improving critical decision-making, and fostering an empowering leadership style.16

The outcomes of this significant investment were not just “soft” improvements in morale; they were measured in hard business metrics that resonated in the boardroom. Following the program, Almi Tankers’ performance benchmarked against the complex ranking criteria of one of the world’s largest oil companies saw a dramatic improvement, jumping from the 43rd position to the 13th position, placing them in the top 1.5% of all cooperating companies.16 This enhanced reputation and proven operational excellence enabled them to secure long-term charter agreements for their entire fleet, even amidst the extreme market volatility of the COVID-19 crisis. Furthermore, the company received numerous prestigious quality and safety awards, including the “Quality Shipping Award for the 21st Century Program” from the United States Coast Guard for all its vessels.16

The Almi Tankers case is a powerful validation of the Human Sustainability framework. Their program directly targeted the development of “inclusive leadership and psychological safety” (Enabler 2), and the results were not confined to internal surveys. The improved customer ranking and the secured long-term charters represent a tangible, multi-million-dollar ROI that justifies the cost of the leadership program many times over. The key takeaway is that leadership is not an abstract, intangible quality; it is a measurable and powerful driver of commercial performance. Investing in changing leadership behaviors from autocratic to empowering has a direct and positive impact on how clients, charterers, and regulators perceive the quality, safety, and reliability of an entire operation.

Subsection 3.3: Proactive Talent Pipelines – Strategic Sourcing and Early Engagement

The case studies of Transpetrol and Almi Tankers focus on developing and retaining existing talent. However, a sustainable crewing strategy must also address the critical challenge of talent attraction. The traditional, passive model of simply waiting for qualified seafarers to apply for vacant positions is proving increasingly ineffective in a world where the maritime industry faces a global shortage of skilled officers and intense competition from shore-based industries.13 Proactive companies are recognizing this reality and are moving “upstream” in the talent pipeline to secure their future workforce.

A compelling example of this proactive approach is provided by AB Crewing. When faced with a specific, acute shortage of Romanian seafarers with the requisite training and experience to operate sophisticated LNG-Gas carriers, the company did not simply broaden its search to other nationalities. Instead, it took a strategic, long-term approach. AB Crewing approached and partnered with local maritime education and training institutions in Constanta to devise and launch a specialized crane driving course and other qualifying programs tailored to the specific needs of their clients’ advanced vessels.5 This initiative not only solved the immediate crewing problem but also created a sustainable, long-term pipeline of qualified local talent for its client, Enzian Shipmanagement.

This practical example is strongly supported by academic research, which emphasizes the critical importance of engaging with potential seafarers at a much earlier stage—specifically, at the secondary school level.7 Such early engagement serves a dual purpose. Firstly, it helps to market the diverse and technical career options available in the modern maritime industry to young people before they have committed to other career paths. Secondly, it provides an opportunity to instill a deeper appreciation for the maritime world and a sense of stewardship for the world’s oceans, fostering a more intrinsic motivation for a maritime career.7 This aligns directly with the GMF’s broader goal of making maritime careers more attractive and accessible to future generations, including women and nationals from developing countries.17

The key takeaway is that the competition for the best talent begins long before a candidate submits a CV. The future viability of any shipping company—and indeed, the industry as a whole—depends on shifting from a reactive recruitment posture to a proactive talent development strategy. This involves forging deep, strategic partnerships with educational institutions at all levels and engaging in early-career outreach to build a robust and sustainable talent pipeline for the decades to come.

Part IV: The Strategic Blueprint: A Framework for Building a Future-Ready, High-Quality Crew

Synthesizing the analysis of the regulatory landscape, the principles of Human Sustainability, and the lessons from industry pioneers, this section presents a comprehensive, actionable framework for senior leadership. This blueprint is structured in four sequential phases, designed to guide an organization on the transformative journey from a traditional, cost-focused crewing model to a modern, value-driven human capital strategy.

Phase 1: Foundational Investment – Redefining the Talent Acquisition & Onboarding Ecosystem

The first phase focuses on building the essential infrastructure and processes required for a modern talent strategy. This involves moving beyond outdated systems and embracing a more strategic approach to how talent is sourced, selected, and integrated into the organization.

- Invest in a Modern Human Capital Management System (HCMS): The reliance on spreadsheets and paper files is a critical vulnerability. The immediate priority must be to invest in and implement a robust HCMS. As demonstrated by the centrality of data systems in the “six enablers” framework, this is the foundational step.15 This system will serve as the single source of truth for tracking granular skills, managing training records, monitoring certifications, and mapping potential career paths, providing the data necessary for all subsequent strategic initiatives.

- Forge Strategic Educational Partnerships: Shift from being a passive recruiter to an active partner in talent creation. This involves moving beyond simple campus recruitment drives to establishing deep, long-term partnerships with select maritime academies and even secondary schools.7 Such partnerships can involve sponsoring cadets, co-developing curricula to address future skill needs (e.g., for alternative fuels or automation), providing guest lecturers, and offering guaranteed sea-time, thereby building a dedicated and loyal pipeline of talent tailored to the company’s specific needs, as exemplified by AB Crewing.5

- Revamp the Onboarding Process: The onboarding process is the first and most critical opportunity to instill the company’s desired culture. It must be redesigned to go beyond administrative paperwork and basic safety briefings. A strategic onboarding program should immerse new hires in the company’s commitment to psychological safety, inclusive leadership, and transparent communication. It sets the tone for their entire career and is the first step in building the trust that underpins high retention rates.15

Phase 2: Continuous Development – From Ad-Hoc Training to Integrated Career Lifecycle Management

With the foundational systems in place, the focus shifts to creating a dynamic and continuous development culture that nurtures talent throughout an employee’s entire career lifecycle.

- Implement a Data-Driven Competency Management System: Drawing directly from the Transpetrol model, develop or adopt a system for the regular, objective evaluation of crew competency.9 This system, whether a formal CES or a bespoke internal tool, should use data to drive decisions regarding targeted training, promotion readiness, and individual development plans. This removes subjectivity, enhances fairness, and provides seafarers with a clear understanding of what is required to advance.

- Develop Proactive, “Beyond-STCW” Training Modules: Actively address the “competency chasm” created by regulatory lag. Do not wait for STCW 2031. Instead, create in-house or partner-led training programs for new fuels and technologies before they become mandatory. This proactive stance not only mitigates operational risk but also turns the regulatory lag into a powerful competitive advantage, positioning the company as a preferred partner for charterers of high-specification vessels.

- Create Transparent, Dual Career Paths: Recognize that the traditional linear path to senior command is not the only definition of success. To retain top technical talent, especially in the engine department, develop a dual career ladder that offers a technical expert track alongside the traditional management track. Furthermore, develop “amphibious skills” training to facilitate seamless ship-to-shore transitions, which can significantly improve long-term retention of highly skilled officers who may seek shore-based roles later in their careers.13

Phase 3: Cultural Integration – Embedding Psychological Safety and Inclusive Leadership

This phase addresses the most challenging, yet most impactful, element of the transformation: evolving the organizational culture. Technology and processes are important, but culture is what ultimately drives behavior and performance.

- Mandate Leadership Transformation Training: Following the Almi Tankers example, make a significant investment in leadership development for all officers and shore-side managers.16 This training must go beyond technical management and focus explicitly on the behavioral competencies of empowering leadership, active listening, providing constructive feedback, and creating an environment of high psychological safety where every crew member feels valued and heard.

- Implement 360-Degree Feedback for Leaders: To ensure accountability and drive real behavioral change, implement a confidential 360-degree feedback system for all leadership positions. This allows leaders to understand their impact on their teams from multiple perspectives and provides objective data for their own development. It holds leaders accountable not just for their technical performance, but for their cultural impact.

- Establish Robust, Anonymous Reporting Channels: Create and actively promote multiple, easily accessible, and truly anonymous channels for seafarers to report concerns related to safety, harassment, bullying, or unethical behavior without any fear of reprisal. Crucially, this system must be backed by a transparent process for investigation and follow-up to demonstrate that all concerns are taken seriously, thereby building trust in the system and the organization.

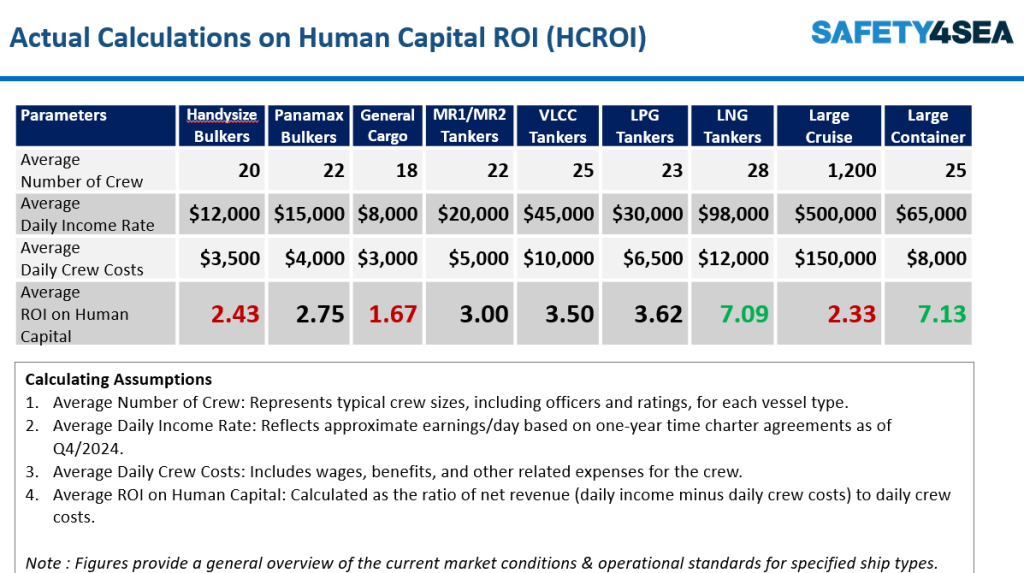

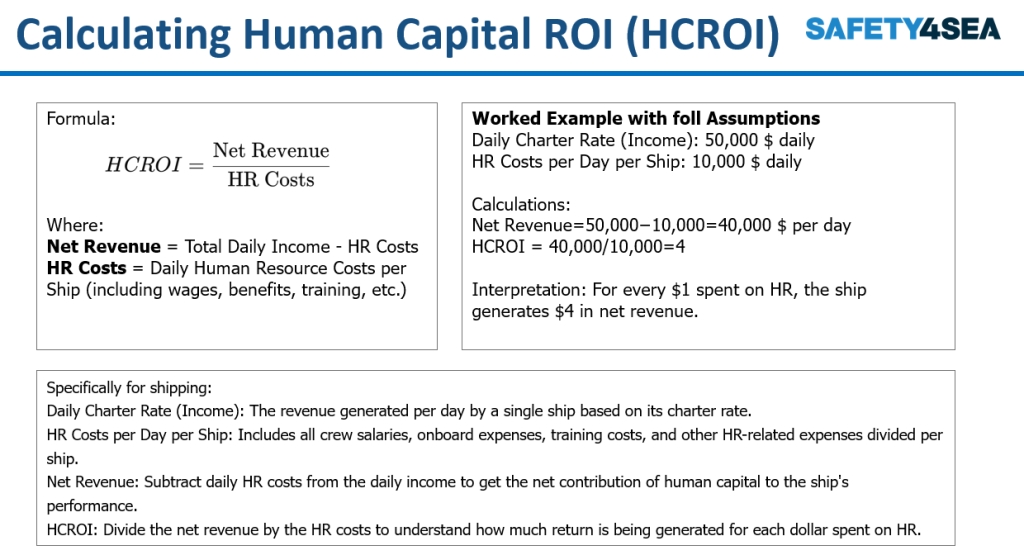

Phase 4: Measuring What Matters – A New ROI Model for Human Capital

The final phase is to institutionalize the new strategy by changing how success is measured. The organization must shift from outdated, cost-based metrics to a new set of value-based Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that accurately reflect the ROI of its human capital investments.

Shift from Cost-Based to Value-Based KPIs: The traditional focus on “Crew Cost per Day” is a dangerous illusion that incentivizes the wrong behaviors. A new, more insightful set of KPIs must be adopted:

-

- Retention Rate (by rank): This is the single most powerful indicator of the health of the company’s culture and the success of its development programs. A high retention rate, as seen at Transpetrol, is a direct financial benefit through reduced recruitment and training costs.9

- Rate of Promotion from Within: This KPI measures the effectiveness of the talent pipeline and succession planning. A high rate indicates a healthy, self-sustaining system.

- Client Performance Rankings / Vetting Observations: This metric, used so effectively by Almi Tankers, directly links crew quality and leadership culture to commercial success and client satisfaction.16

- Lost Time Injury Frequency (LTIF) / Total Recordable Case Frequency (TRCF): These safety metrics provide a direct measure of the effectiveness of investments in safety culture, fatigue management, and psychological safety.16

- Training ROI: Develop methodologies to calculate the tangible return on specific training investments, comparing the program’s cost to the value of a secured charter, a prevented incident, or improved operational efficiency.

Create a Human Capital Dashboard for the Board: These new KPIs should be consolidated into a strategic “Human Capital Dashboard” that is reviewed regularly at the board and senior executive level. This elevates the conversation about crewing from a tactical, operational concern to a strategic, board-level priority, continuously reinforcing the link between investing in people and achieving superior financial returns.

Conclusion: Charting the Course for Sustainable Success

The era of treating seafarers as a disposable commodity or a manageable cost is definitively over. The confluence of profound technological disruption, escalating regulatory complexity, and a tightening global market for talent has exposed the fatal flaw in a strategy based on cost-minimization. The evidence presented throughout this report is clear and compelling: the shipping companies that will survive and thrive in the coming decades will be those that reject the “illusion” that people are an expense and fully embrace the “insight” that they are the single most critical investment for future success.

The journey from a compliance-driven safety culture to a value-driven Human Capital ROI model is neither simple nor swift. It demands significant financial investment, unwavering long-term commitment from the highest levels of leadership, and a fundamental, often difficult, shift in organizational mindset. However, as the pioneering case studies of companies like Transpetrol and Almi Tankers demonstrate, the returns are not theoretical; they are tangible, measurable, and substantial. They manifest in the form of operational excellence, enhanced commercial resilience, superior safety performance, and a truly sustainable future in an industry defined by change.

The choice for industry leaders is therefore no longer if they should make a strategic investment in their people, but rather how quickly they can begin to implement the transformative changes necessary to secure their position as leaders in the new maritime era. The course has been charted; the time to set sail is now.

Seafarer Club compiled and translated with the support of Gemini AI

Works cited

- IMO policy measures: What’s next for shipping’s fuel transition? – Global Maritime Forum, accessed September 3, 2025, https://globalmaritimeforum.org/insight/…fuel-transition/

- IMO Maritime Safety Committee (MSC 110) – DNV, accessed September 3, 2025, https://www.dnv.com/news/2025/imo-maritime-safety-committee-msc-110/

- MSC 110 – Eagle.org, accessed September 3, 2025, https://ww2.eagle.org/content/dam/…Brief.pdf

- Maritime Safety Committee – 110th session (MSC 110), 18-27 June 2025, accessed September 3, 2025, https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/MeetingSummaries/Pages/msc-110th-session.aspx

- Case studies | Crewing Services & Ship Management for the Globalized Seas, accessed September 3, 2025, https://abcrewing.com/clients-zone/case-studies/

- IMO Sub-committee on human element, training and watchkeeping (HTW11) – DNV, accessed September 3, 2025, https://www.dnv.com/news/2025/…watchkeeping-htw11/

- Sustainable Maritime Career Development: A case for Maritime Education and Training (MET) at the Secondary Level – ResearchGate, accessed September 3, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/…_and_Training_MET_at_the_Secondary_Level

- Amendments to IMO instruments: upcoming and recent entry into force/effective dates, accessed September 3, 2025, https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/Amendments-to-IMO-instruments.aspx

- News Content Hub – Transpetrol: A case study in tanker … – Riviera, accessed September 3, 2025, https://www.rivieramm.com/news-content-hub/….crew-training-61860

- Human Sustainability | Global Maritime Forum, accessed September 3, 2025, https://globalmaritimeforum.org/human-sustainability/

- Human sustainability programme | Global Maritime Forum, accessed September 3, 2025, https://globalmaritimeforum.org/human-sustainability-programme/

- Global Maritime Forum: Human sustainability is a business imperative – Safety4Sea, accessed September 3, 2025, https://safety4sea.com/cm-global-maritime-forum-human-sustainability-is-a-business-imperative/

- Emerging Dynamics of Training, Recruiting and Retaining a Sustainable Maritime Workforce: A Skill Resilience Framework – MDPI, accessed September 3, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/16/1/239

- 2022 – Global Maritime Issues Monitor, accessed September 3, 2025, https://www.maritimeissues.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/GMF_Issues2022_FINAL.pdf

- Diversity@Sea: Building Sustainable Maritime Crewing – Synergy Marine Group, accessed September 3, 2025, https://www.synergymarinegroup.com/sustainability/diversity-at-sea/

- Almi Tankers S.A. Leadership Programme: a case study, accessed September 3, 2025, https://www.sbs.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2021-06/almi-tankers-in-depth-case-study.pdf

- Navigating towards an inclusive and sustainable maritime future: Perspectives of young professionals, accessed September 3, 2025, https://globalmaritimeforum.org/insight/navigating-towards-an-inclusive-and-sustainable-maritime-future/